Proper Error Handling

Modern software is often complex. Such complexity usually manifests in various forms, such as many dependencies, internal shared libraries, monoliths, and distributed monoliths. However, complexity is also a set of bad technical decisions resulting from complex business rules and a lack of comprehensive integration tests.

Fail Fast vs Fail Safe

There are basically two ways we can handle software errors. The first option is called Fail Fast. This means we throw an exception or error to break the application by design when something is missing, such as a parameter, value, or state. The Erlang/Scala community is famous for using a philosophy often called "Let it crash". Where the assumption is IF you let the application crash and restart with a clean slate, there is a good chance the error go away.

Fail-safe; conversely, try to "recover" from the error. NetflixOSS was famous for applying this philosophy with a framework called Hystrix, where the code was wrapped around commands, and such commands always had a fallback code. Amazon is famous for preferring to double down on the main path rather than focusing on fallbacks.

Now, no matter if we are more into fail-fast or fail-safe. You need to have proper integration tests to ensure you trigger or activate the non-happy paths of the code. Otherwise, you don't know if you code it right, and you will discover in production eventually in the most expensive form for you and the final user. Now, what should I do? Here is my guidance.

Fail Safe vs. Fail Fast Recommendations:

- Fail Fast (make the application crash when):

- Critical information is missing or wrong, i.e, the URL of a downstream dependency.

- Avoid picking a default value when it could introduce a performance bottleneck. i.e numThreads, if you can't parse a number, don't assume 3, for instance.

- Do not crash the application for allowed optional parameters. i.e, optional driver's license for a 3% discount.

- Fail Fast can be annoying, but it will be visible to Operations and easily spotted and can be handled.

- Fail-Safe (try to recover):

- IMHO, to apply such techniques and philosophy, you must have it explicitly on the business rules. i.e, if the driver's license is present, apply a 3% discount; in that case, it might be fine to have the driver's license and an empty or default value since the business rules predict

- Don't assume upstream will be fine (returning an empty string, null, or negative values). Unless the business rules allow it.

- IF fail-safe is misapplied, it will result in nasty, hidden bugs that take hours to debug and fix. So you need to be more careful when making this choice.

- Regardless of philosophy, all branches and scenarios should always cover integration tests.

- Configuration Testing is a great idea to avoid production bugs and nasty surprises; consider having a central class to handle all configs so testing is pretty easy for external configs.

- Some failure and chaos scenarios require induction and state assurance if applied in a certain way. You either need to have testing interfaces in your consuming services, or you need to use them internally. Here is a post where I shared more about testing queues and batch jobs.

Exception vs Errors

Exceptions are usually used "internally" and errors "externally." Consider you have a proper service; inside the service (of course, it depends on the language), you will have exceptions, and in the contract to the outside, you will have errors, considering HTTP/REST interfaces, for instance.

Some languages have both, or you could have different frameworks that handle other things. For instance, when you use a centralized log solution, you can log exceptions and errors; IMHO, you should leverage exceptions as much as possible because they have more context due to a stack trace. One common mistake is to log exceptions incorrectly, resulting in having only the message on the centralized logging solution, so you need to make sure you are sending the stack trace to the centralized log solution.False Positives and False Negatives

When doing error handling, we can have 4 scenarios.

True negative is when it is not an error/exception. True positive is when there is an error/exception. False positive is when it looks like an error/exception but is not. A false negative is when it seems like that is not an error but actually is.

Stack traces are good for troubleshooting and investigation, but you do not want to be investigating at all times; you need to be investigating when you don't know what's happening; most of the time, it should be knowing exactly what's going on. What this means? It means that, as much as you know your application/service when it works, you should know when it does not. Some people call this failure mode; you must know how your application can and precisely when each failure is happening (which is better handled with testing).

Signal vs Noise

Signals can bring clarity and meaning. While noise is just obscurity or a mystery. When observing your services in production, you want to know immediately what's going on. You want to maximize understanding, so you want to know what's going on very fast. IF your service throws hundreds to thousands of exceptions daily, it will be hard to make sense of it. That's why you want to monitor it very closely and improve error handling and observability daily.

Like I said before, it's great to have stack traces in a centralized log, but the more you need to use them, the less signal you have. You should have a proper exception metric that clearly signals what is going on.

Nature of Computation

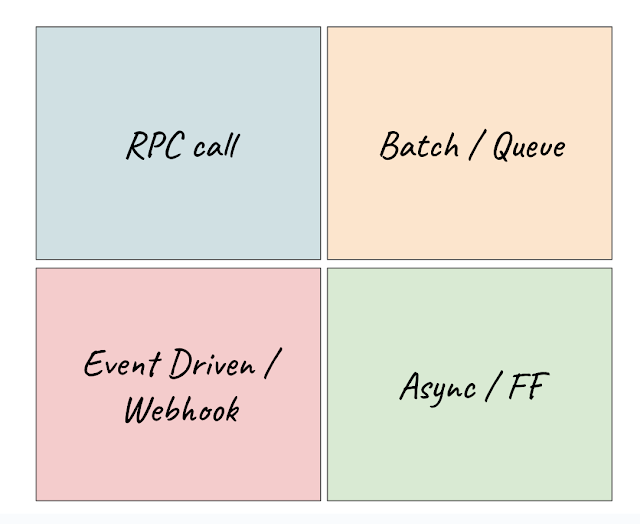

Service cannot be that different at the end of the day. There are just a few other patterns of computations and things that can be happening; here is one example.

RPC Call: The most common service that performs RPC calls to other services. So the most common scenarios of error handling here are:- Upstream: who is calling you? What timeout do they have? Is your service timing out?

- Downstream: your service calls other services; questions for error handling and monitoring are: are they timing out? Are they giving you 500x errors?

Improving Error Handling

Error handling can be improved; here are some practices you can do to get it better:

- Review error handling as part of code review.

- Review exceptions in production dashboards every day.

- Be clear about what is happening, and provide more details when logging in.

- Log information context (IDs, variables, times).

- Log full exception stack traces.

- Don't swallow exceptions unless narrow and 100% sure they are okay.

- Understand what is an error vs. normal behavior(don't throw exceptions):

- The user was not found (user type fgdjhdsfljkhsdljkf), so don't log it.

- Always make sure you can retry

- When using a Queue => DLQ or table for errors

- When a service is down? (use queue or table)

- IF you are not using distributed tracing. Always log some form or correlation id (otherwise, how do you use 1 vs 2?)

- Avoid returning null

- Make sure logs are symmetrical. If there is a start, it should have an end.

- Make sure you log after/before every major step; otherwise, how do you know where the issue is (i.e., log(), step1(), step2(), step3(), -- where is the issue?)?

- Make sure it validates and sanitizes all mandatory requests/parameters. Throw proper Exceptions.

- Queues, Files, Pools need to be specific and never generic (especially when there are multiple), i.e, queue1 vs queue2?

- You should know how long everything takes (it is not dapper). Log it all (time in ms)

Cheers,

Diego Pacheco